Interview: Filmmaker Michael Caplan

By Rob Christopher in Arts & Entertainment on May 18, 2009 5:20PM

A hundred years after he was born, could Nelson Algren finally be getting some of the respect he so richly deserves?

A hundred years after he was born, could Nelson Algren finally be getting some of the respect he so richly deserves?

An unprecedented interest in Algren's work has been percolating all spring: a star-studded evening at Steppenwolf celebrating the author, a previously unpublished story gracing the Reader and a brand-new collection of his writings. But, as David L. Ulin insightfully notes, "it's an open question as to whether he would have recognized this new Chicago, although the city seems intent on recognizing him." His depictions of the hard-luck losers who lived on the Near West Side and Wicker Park seem far removed from the Real World-ready environs of today.

Still, great writing such as Algren's can't stay obscure forever, and Columbia College professor and filmmaker Michael Caplan is doing his part to shine some light on the author's life and times by creating a documentary. We caught up with him during pre-production on the film to discuss his personal connections with Algren's work and the surprising ways in which it's influenced everyone from Kurt Vonnegut to Lou Reed.

Chicagoist: Why a documentary about Nelson Algren? What's your personal history with Algren's work?

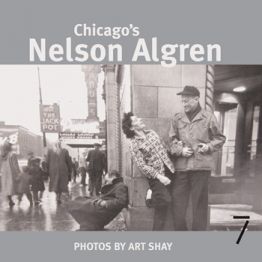

Michael Caplan: I met photographer Art Shay at a photo exhibit last year. Shay was a great friend of Algren's, and he's photographed much of the time he spent with him roaming the streets of Chicago. Growing up on the Southeast Side of Chicago, I'd always been an Algren fan. To me he was an entryway into all those things and people I wasn't supposed to know about as a kid: drugs, sex, hookers and gambling. Art and I discussed my making a documentary about the man using his black and white photos, although the overall concept for the film has really expanded over the past year with the arrival of Nelson's centennial.

C: Who are you planning on interviewing? What sort of archival footage of Algren exists?

MC: Ultimately Algren was a solitary man, but he had a lot of friends and supported a lot of young writers in his time. I plan on interviewing people who have achieved great things artistically and who were Algren's peers or inspired by his work, in some cases both. Of course Art Shay is on the list, Chicago newspaperman Rick Kogan, local fiction writers like Joe Meno and Don DeGrazia. I'd love to get Hefner involved in the project—Algren had several pieces published in Playboy—as well as producers and writers for the TV series The Wire, people like Richard Price and George Pelecanos. I'm a big fan of The Wire and find the writing so reflective of Algren's gritty style. Director Philip Kaufman actually put Algren in two of his early films, a 1967 film called Fearless Frank that also starred Jon Voight, and Goldstein, which was made in 1965 and has Nelson playing himself. Several musicians have also come to mind:Tom Waits, Jeff Tweedy, Lou Reed, who lovingly ripped off "A Walk on the Wild Side" directly from Mr. Algren (I say that with the utmost respect). You begin to see the extent of Algren's influence with this list. As far as archival footage, there are a few interviews with people like Kurt Vonnegut and Norman Mailer talking about the importance of Algren's work, as well as some old television footage of Algren leaving Chicago. Simone de Beauvoir, with whom Nelson had a famously tragic love affair, has an adopted daughter who still has some unpublished letters to Simone from Nelson, which I'd love to get access to. There is a wealth of resources and no shortage of individuals who were or are greatly indebted to Algren's writing.

C: Did Algren's run-in with Preminger over The Man with the Golden Arm sour him against the movie business for the rest of his life?

MC: Algren felt that Frank Sinatra's portrayal of Frankie Machine did the true character no justice. He didn't like Kim Novak. He thought the whole thing was crap, and quite possibly turned him off the movie business. Art Shay has a story about asking Algren to pose under the marquee for The Man with a Golden Arm and Algren said, "What does that movie have to do with me?" Algren wanted only to write. He didn't play the Hollywood game and, when he was paid far too little for the rights to the novel, he bought a house and didn't make a very good landlord either. He was a writer.

C: Why isn't he more widely-read today? Why doesn't he have the stature of Hemingway or even Jim Thompson, for example?

MC: Well, I can only guess that his rejection by the academe and the literary establishment had its effect. He was honest and irreverent and maybe got under people's skin. Nelson tried many times, unsuccessfully, to apply for a Guggenheim and never got it. Ernest Hemingway was actually a big fan of Algren's, but his books never went out of print. By 1983 Algren's books, all except Chicago: City on the Make, were out of print. Now a New York publishing house called Seven Stories Press, which just released Algren's unpublished novel and several other stories called Entrapment and Other Writings, puts out Algren's books. So hopefully we'll see a resurgence. I hope to create more interest with this film.

C: What would Nelson think about Chicago today?

MC: When he left Chicago for New Jersey in 1975 he certainly had no love for the city. He felt it had rejected him, failed to recognize his work. Plus by the end of his life he was pretty bitter and drinking a lot. But I don't wish to focus on that with this movie. I want to show that ultimately he was a compassionate man who loved people, especially the underdogs. And I think that, if Nelson were to come back from the dead, he would see a lot in Chicago to make him happy. Maybe he wouldn't recognize the Wicker Park and Ukrainian Village he knew, except for a few small dive bars. But I think he would appreciate the thriving literary culture we have here now—the numerous reading series, the several small independent presses publishing new local writers, the festivals and book fairs—most of which are started by writers themselves. I think there's definitely a lot in Chicago that might change his mind about how it values its writers, and certainly he would be delighted to know about the recognition he's gaining in Chicago now during his centenary.

C: Once the documentary is finished, what are your plans for distribution?

MC: Well, the festival circuit is so clogged that filmmakers are finding different, creative ways to get their films seen, one of which is through online distribution. Right now I'm looking for distribution for my recently completed doc, A Magical Vision, and am seeking out screening opportunities across the country. It's a tough market, but every film has its niche. With all the enthusiasm I've encountered for Algren thus far, I don't think there will be a shortage of interest.